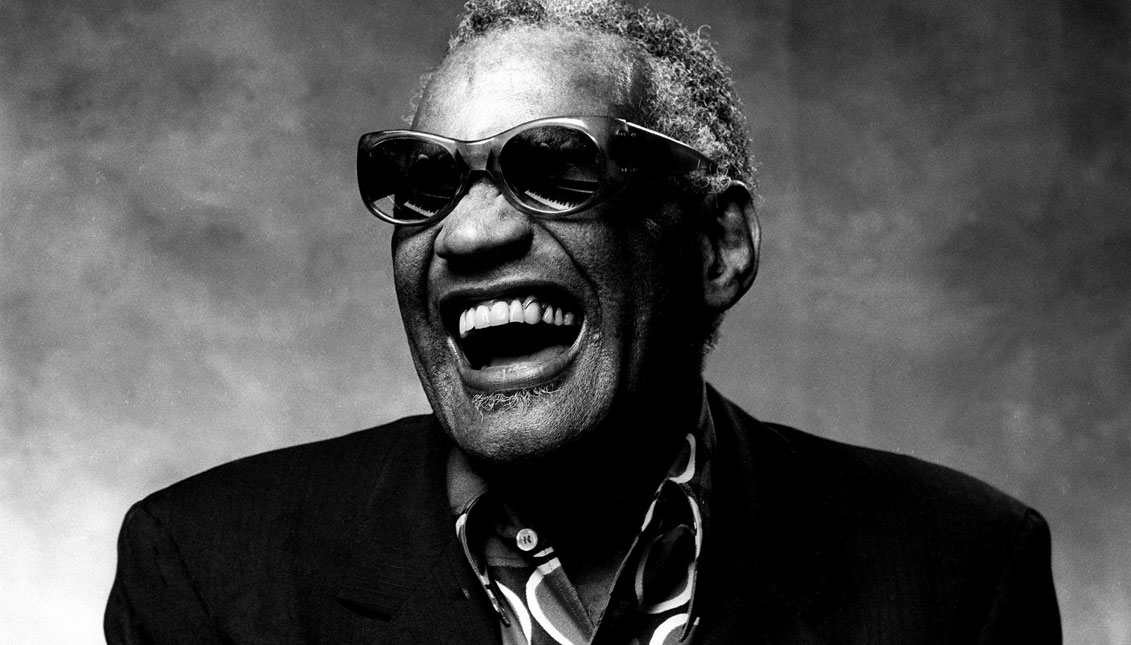

Remembering Ray Charles, hallelujah, we love you so

The father of soul left his mark with the creation of a new genre, went down to hell, knew glory and was flattered by the greats of his time.

Only Ray Charles (September 23, 1930; June 10, 2004) carries the medals of honor of having been called by Frank Sinatra "the only genius in the business" and by Aretha Franklin "the right reverend." This is because Ray Charles took the rhythms and prayers of gospel music to make sacred music join the profane and created soul.

One of the most obvious and memorable moments in which this happened was when What I'd Say was born, in December 1958, during a four-hour performance with his band - a usual length for the time, according to the Rolling Stone - and missing the last fifteen minutes they ran out of repertoire.

Charles told his musicians and the Raelettes, the chorus girls who accompanied him, to go along with it and sat down at the piano to improvise the basis of a melody that, when answered by the drummer, would be the germ of his first gold record: a long, two-part song recorded by Atlantic Records that has no way of leaving anyone indifferent.

The Raelettes did the same, following the structure of the gospel in which the preacher declaims or sings a verse and the community responds. But Charles' preaching was not a praise to God, but the closest thing to a choral orgasm.

The "ummmmh" and "unnnnh" that at first are long moans shorten as the song progresses and Ray Charles and the Raelettes respond to each other all the way up to climax.

Charles recounted for the rest of his days that on the spot the audience stood up to dance and asked him where they could buy that record, the profane miracle, the choral orgasm.

A year later, when the LP was pressed and released, it was a success.

RELATED CONTENT

Comments abounded about how unseemly those moans were, about all the cheeks he was blushing, and Charles dismissed it as sanctimonious. "Hell, let's face it, everybody knows about the ummmmh, unnnnh. That's how we all got here," he told Rolling Stone in 1978.

In several of his songs he returned to the gospel to take up expressions that worked profane wonders, such as turning "This little light of mine" into "This little girl of mine" or referring to his neighbor in terms often used to speak of the relationship between a faithful believer and Jesus Christ.

When I'm in trouble and I have no friends,

I know she’ll go with me until the end.

Ev'rybody asks me how I know.

I smile at them and say she told me so.

That's why I know, yes, I know,

Hallelujah, I just love her so.

It is true that he lost his sight at the age of seven, that he was orphaned young, starved, a heroin addict and a womanizer, but what made him so great was not his descent into hell, but the way in which - as so many artists have done - he picked up his cultural heritage to make way to a new language.

In interviews he refused to tell his story of drug abuse because he did not believe in uplifting stories and it is not worth insisting on that point. What is worth insisting on is listening to him, from his best known songs - like the ones already mentioned - to his instrumental jazz collaborations.

And to listen once and again the way men have used divine language to say the worldly.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.